“I lived in this house exactly half a lifetime ago,” said Bruce Springsteen. It may not look like much, but this small bedroom in Colts Neck, New Jersey, which still sports the original orange shag rug, is where Springsteen made what he considers his masterpiece: his 1982 album “Nebraska,” ten songs dark and mournful. “This is the room where it happened,” he said.

I saw her standing on her front lawn just twirling her baton

Me and her went for a ride, sir, and ten innocent people died

From the town of Lincoln, Nebraska, with a sawed-off .410 on my lap

Through to the badlands of Wyoming I killed everything in my path

“If I had to pick one album out and say, ‘This is going to represent you 50 years from now,’ I’d pick ‘Nebraska,” he said.

It was written 41 years ago at a time of great upheaval in Springsteen’s inner life: “I just hit some sort of personal wall that I didn’t even know was there,” he said. “It was my first real major depression where I realized, ‘Oh, I’ve got to do something about it.'”

“And you can’t succeed your way out of pain,” said Axelrod.

“No, you cannot. That’s a very good way of putting it; you cannot succeed your way out of that pain.”

Coming off a hugely successful tour for “The River” album, he had his first Top 10 hit, “Hungry Heart.” He was 32, a genuine rock star surrounded by success, and learning its limits.

Axelrod said, “Your rock ‘n’ roll meds, singing in front of 40,000 people, all that is, is anesthesia.”

“Yeah, and it worked for me,” Springsteen said. “I think in your 20s, a lotta things work for you. Your 30s is where you start to become an adult. Suddenly I looked around and said, ‘Where is everything? Where is my home? Where is my partner? Where are the sons or daughters that I thought I might have someday?’ And I realized none of those things are there.

“So, I said, ‘OK, the first thing I gotta do as soon as I get home is remind myself of who I am and where I came from.”

At the fixed-up farmhouse he was renting, he would try to understand why his success left him so alienated. “This is all inside of me,” he said. “You can either take it and transform it into something positive, or it can destroy you.”

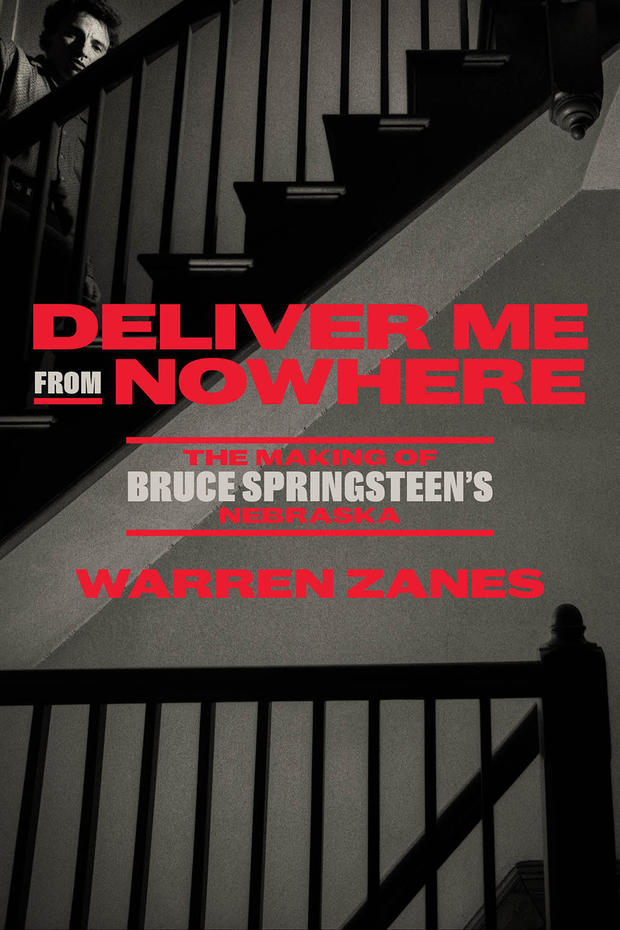

Author Warren Zanes said, “There are records, films, books that don’t just come in the front door. They come in the back door, they come up through a trap door, and stay with you in life.”

Zanes’ new book, “Deliver Me from Nowhere,” offers a deep and moving examination of the making of “Nebraska.”

Springsteen’s pain was rooted in a lonely childhood. “Here’s Bruce Springsteen making a record from a kind of bottom in his own life,” said Zanes. “They were very poor. And then he becomes Bruce Springsteen. He felt that his past was making his present complicated. And he wanted to be freed of it.”

For Springsteen, liberation had always come through writing. While he filled notebook after notebook (“It’s funny, because I don’t remember doing all this work!” he mused, leafing through his writings), the album didn’t come together until late one night when he was channel surfing and stumbled across “Badlands,” Terrence Malick’s film about Charles Starkweather, whose murder spree in 1957 and ’58 unfolded mainly in Nebraska. He said, “I actually called the reporter who had reported on that story in Nebraska. And amazingly enough she was still at the newspaper. And she was a lovely woman, and we talked for a half-hour or so. And it just sort of focused me on the feeling of what I wanted to write about.”

In a serial killer, Springsteen had found a muse:

I can’t say that I’m sorry for the things that we done

At least for a little while, sir, me and her, we had us some fun …

They wanted to know why I did what I did

Well, sir, I guess there’s just a meanness in this world

“‘There’s a meanness in this world.’ That explains everything Starkweather’s done,” said Axelrod.

“Yeah, I tried to locate where their humanity was, as best as I could,” Springsteen said.

In a surge of creativity, he wrote 15 songs in a matter of weeks, and one January night in 1982, it was time to record, on a 4-track cassette machine. One of rock’s biggest stars sat in this bedroom, alone, and sang, getting exactly the sound he was looking for.

And the acoustics? “Not bad,” Springsteen said. “The orange shag carpet makes it really dead. Not only was it beautiful to look at, it came in handy!”

Some songs explored the confusion left from childhood, like “My Father’s House”:

I walked up the steps and stood on the porch

a woman I didn’t recognize came and spoke to me

Through a chained door

I told her my story and who I’d come for

She said “I’m sorry, son, but no one by that name

Lives here anymore”

Springsteen said, “‘Mansion on the Hill,’ ‘My Father’s House,’ ‘Used Cars,’ they’re all written from kids’ perspectives, children trying to make sense of the world that they were born into.”

Others profiled adults left out, or left behind. The music, Springsteen maintained, possessed a “very stark, dark, lonely sound. Very austere, very bare bones.”

On a broken-down boom box, Springsteen mixed the songs onto a cassette tape he carried around in his back pocket, for a few weeks. “I hope you had a plastic case on it, at least,” said Axelrod.

“I don’t think I had a case,” he replied. “I’m lucky I didn’t lose it!”

Springsteen’s band would record what he had on the cassette, but bigger and bolder wasn’t what he was looking for: ”It was a happy accident,” he said. “I planned just to write some good songs, teach ’em to the band, go into the studio and record them. But every time I tried to improve on that tape I had made in that little room? It’s that old story: if this gets any better, it’s gonna get worse.”

Bruce Springsteen wasn’t working E Street, but another road entirely. According to Zanes, “‘Nebraska’ was muddy. It was imperfect. It wasn’t finished. All the things that you shouldn’t put out, he put out.”

Everything dies, baby, that’s a fact

But maybe everything that dies some day comes back

Put your makeup on, fix your hair up pretty

And meet me tonight in Atlantic City

Axelrod asked, “Did any part of you worry, ‘Oh my goodness, what am I putting out there?'”

“I knew what the ‘Nebraska’ record was,” Springsteen said. “It was also a signal that I was sending that, ‘I’ve had some success, but I do what I want to do. I make the records I wanna make. I’m trying to tell a bigger story, and that’s the job that I’m trying to do for you.'”

A few more songs that didn’t make the cut? You probably heard them later, including “Born in the U.S.A.,” “Pink Cadillac,” and “Downbound Train” – songs the guy in the leather jacket who’d written of chrome-wheeled fuel-injected suicide machines kept in a binder with Snoopy on the cover.

In that small bedroom, Springsteen the rocker made an album that fleshed out Springsteen the poet. Imagine for a moment if he hadn’t. Axelrod mused, “And then people might be assessing a career and say, ‘Oh, it was great, man, 70,000 people singing “Rosalita” in the stadium.’ But that might have been closer to where it ended in considering what you’ve done.”

“Yeah. I was just interested in more, in more than that,” Springsteen said. “I love doin’ it. I still love doin’ it to this day. But I wanted more than that.”

“If they want to enjoy your work, try anything; if they want to understand your work, try ‘Nebraska’?” asked Axelrod.

“Yeah, I’d agree with that,” he replied. “I’d definitely agree with that.”

Source: cbsnews